Horse Whispering

I confess that, when I allow myself to think about it, I am amazed that I understand so little about what it is we philosophers do. I believe I can distinguish good philosophical work from bad—I can recognize when philosophy is done well—but I do not have a clear understanding of what it is that I am recognizing, and when I try actually to say what our discipline does, my remarks turn out to be naive and crude, more like the groping efforts of a beginning student than like the contributions of an advanced scholar to the field.

The confession is Matt Boyle’s, in a talk delivered at a retirement conference for John McDowell, with whom I was proud to be a colleague at the University of Pittsburgh for 13 years.1

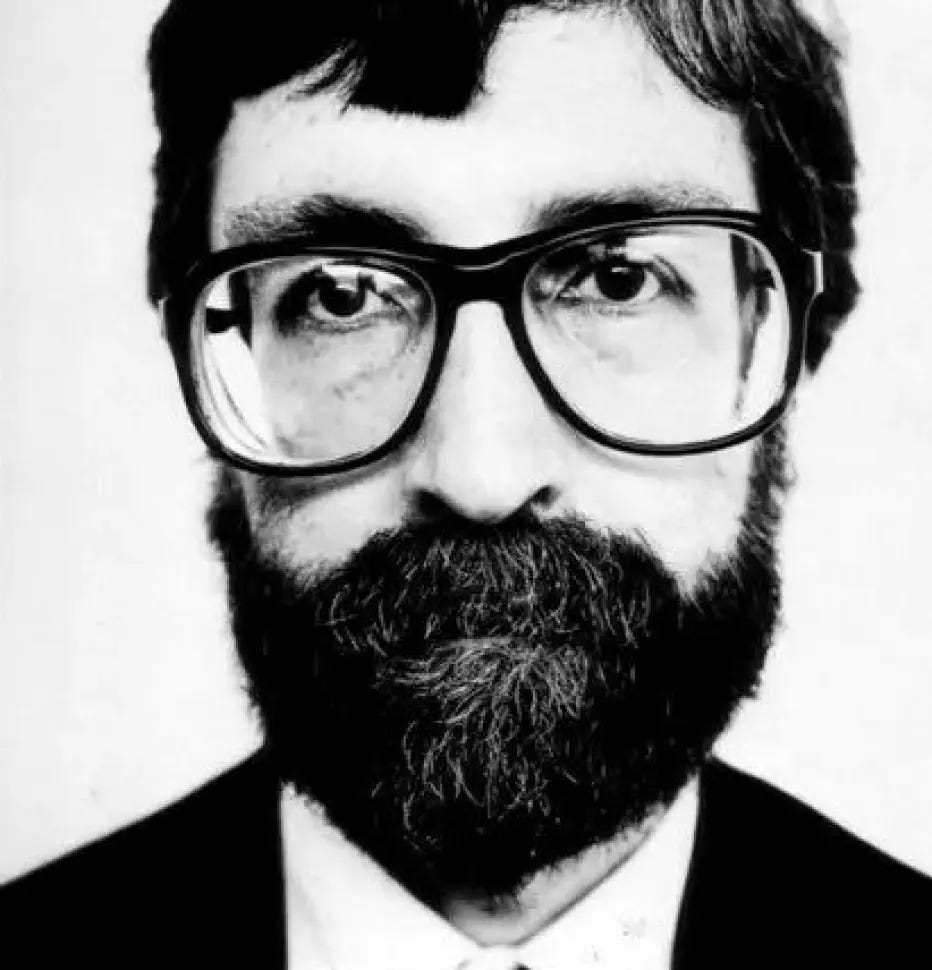

The title of Matt’s remarks was “McDowell on Method” and their premise was that McDowell is one of the few who does not sound like a beginning student in his rare pronouncements on “metaphilosophy.” Boyle opens with the text that accompanied Steve Pyke’s photo of McDowell in an impressive album of the furrows, facial hair, and crow’s feet of the great philosophers:

My main concerns in philosophy centre on the effects of a metaphysical outlook into which we easily fall, at the point in the history of thought that we occupy. This outlook might be called naturalism or scientism. I believe it tends towards a distortion of our thinking about the place of mind in the world: the damaging effects show up not only in metaphysics itself, but also (for instance) in reflection about language, and in the philosophy of value and action. The task of philosophy, as I see it, is to undo such distortions.

Boyle’s main interest is the form in which these distortions express themselves, for McDowell: an intellectual cramp or constriction that compels the question, “How is this so much as possible?”—where this might be empirical knowledge, objective value, or intentional action.

McDowell’s insight, in the introduction to Mind and World, is that such questions sound like an invitation to constructive theory, as though we are to explain the mechanics of mind and world through a feat of philosophical engineering, but they in fact derive

from a frame of mind that, if explicitly thought through, would yield materials for an argument that what the questions are asked about is impossible.

Until one exposes the argument, one does not really understand the question one is asking, at which point, one’s task is to explain where the argument goes wrong. If one succeeds, the question vanishes. There is no occasion, in this process, for theory-building, as opposed to therapy.

Like Boyle, I am sympathetic to this attitude, though I think I learned it first not from McDowell but, oddly enough, Hugh Mellor, a metaphysician McDowell might well accuse of fabricating castles in the sky.2 I gave it as one of my few rules of method in philosophy when I wrote about Ronnie O’Sullivan and the question “How is what he does so much as possible?” But, like Boyle, I think there’s something missing from McDowell’s vision.

I say this with trepidation, since engagement with McDowell’s work can be treacherous: he is notoriously severe even with those who intend to be in concert with him. McDowell replied to an essay by Robert Brandom whose second sentence was “I think everything [McDowell] says is true and important” by complaining that Brandom’s “representation of me fails to achieve even the status of a caricature—which would require a recognizable likeness.” McDowell compares his rejoinder to “the small explosion emitted by a bombardier beetle to avoid being swallowed by a predator.” And, in a footnote:

I am resisting being cast as the hind legs of a pantomime horse called “Pittsburgh neo-Hegelianism.”

There is an equestrian theme to McDowell’s self-defence. When Brandom published his long-awaited book on Hegel, A Spirit of Trust, McDowell commented:

Brandom dedicates his book to me. He will not be surprised at my looking this gift horse in the mouth.

Duly warned, I offer a disclaimer: McDowell’s remarks were not intended as a comprehensive picture of philosophy. We should be pluralistic about the questions that we count as philosophical—seemingly profound but not amenable (yet?) to proprietary methods and results. Some of these questions become tractable over time, generating novel disciplines. Others test the bounds of metaphysics. Some ask “How is this so much as possible?” And when they do, their answers won’t explain “how-to” but bring us to protest, “Why not?”

Boyle objects, first, not to the letter but the spirit of McDowell’s “quietism”:

I agree with McDowell that a compelling “how possible?”-question rests on some apparent threat to the possibility of a given phenomenon—some aporia, as ancient philosophers would say. What I want to add is that compelling aporias are among the most precious things in philosophy.

We should welcome our perplexities with gratitude, not wish them away. For they are not mere confusions or manifestations of error, but tensions any thinker can be brought to feel. The premises that generate the problem “How is this possible?” present themselves “as aspects of what any of us can already see to be true about a given topic when we take things at face value.”

Where do such “intuitions” come from? Why are they so persistent? “The only account I know of that really speaks to this question,” Boyle writes, “is a broadly Kantian one, according to which [they] have their roots in aspects of the form of our own power of cognition.” On this conception, philosophy does not merely undo misunderstanding, as McDowell suggests; it sheds positive light.

“What such intuitions have to teach us,” Boyle concludes, “are not hitherto unknown facts but points about the form of our own cognition that we already grasp in a non-propositional way.”

Indeed, nothing rules out the idea—which I take to have been the view of the historical Kant—that philosophical inquiry can discover a systematic order in our knowledge of our own power of cognition, an order that gives us insight into the most fundamental grounds of our intuitions and of the aporias and antinomies to which they seemingly give rise.

Boyle’s argument gets to the root of the matter: whether questions of possibility disclose deep truths or manifest local distortions. Boyle is cognizant of the latter alternative—witness the text McDowell supplied to Pyke, about the scientism “into which we easily fall, at the point in the history of thought that we occupy.” McDowell hopes to reclaim our original innocence.

Boyle argues against historical locality in the specific case of perceptual knowledge that is the subject of Mind and World. He may be right, but I wonder if he has missed another moment of “quietism,” inspired by “resolute” readings of the early Wittgenstein, on which the insights taught by intuition are not merely ones “we already grasp in a non-propositional way” but can only be grasped in that way. If we learn something about our own power of cognition in asking “How is this possible?” does the knowledge we gain as the question is dissolved take the form of systematic theory or practical know-how?

My own complaint about McDowell points in a different direction. It’s that “how possible?"-questions are at most one species of the genus that explores the bounds of metaphysics. We also ask, “Why is this impossible?” What in the nature of intentional action makes it impossible to act for reasons when you have no idea what you are doing? What in the nature of knowledge or belief makes it impossible to know what you don’t believe? What in the nature of belief makes it impossible to have just one of them—why must beliefs come as package deals?

The answers to these questions, I think, take the form of “real definitions” or statements of what it is to act intentionally, or to know, or to believe, that entail the relevant impossibilities: that they are impossible follows from the natures of things. Or, if it doesn’t, then what seemed impossible isn’t really. Maybe to know is to have a true belief whose justification is indefeasible? Or if that’s wrong, to believe is to manifest, perhaps defectively, the capacity to know? Or, if that’s wrong, maybe you can know what you don’t believe?

McDowell reads as a “quietist” about the question “Why impossible?” as much as he is about the question “How possible?” He rejects the project of constructive philosophical theory involved in stating real definitions. This comes out in his attitude to circularity. If circular definitions are permitted, the task of explaining why things are impossible becomes trivial.

Q: Why can’t you know what you don’t believe?

A: Because to know something is, in part, to believe it.

Q: Yes, in part—but what’s the rest?

A: That can’t be specified except in terms of knowledge. To know something is to believe it knowledgeably. That’s why you can’t know what you don’t believe.

I don’t think this is a good answer to the question of impossibility. Like nominal or verbal definitions, “real definitions” cannot be in this way circular.

As I interpet him, McDowell rejects that constraint and thus the substantive project of philosophical analysis, understood in metaphysical terms. Pressed to explain the necessary relations between values and sentiments, on the model of “secondary qualities” like red, he opts for a “no-priority” view:

It is implausible that looking red is intelligible independently of being red; combined with the account of secondary qualities that I am giving, this sets up a circle. But it is quite unclear that we ought to have the sort of analytic or definitional aspirations that would make the circle problematic.

What about a position that says the extra features [i.e. values] are neither parents nor children of our sentiments, but—if we must find an apt metaphor from the field of kinship relations—siblings?

If we are allowed to insist that knowledge and belief are coeval, to refuse to explain one in terms of the other except with circularity—and to do the same for values and sentiments, reasons and causes—we lose the impetus to a form of systematic theory in philosophy that I, for one, find difficult to resist.

I don’t know how to establish, or even state, the ban on circular definitions, and I expect that McDowell would welcome the loss of impetus its rejection brings. But I can add, to my few rules of method in philosophy, not just that the question of possibility presupposes an argument that it isn’t possible, whatever it might be, but that claims of impossibility call for constructive metaphysical inquiry into the nature of mind or world.

Thanks to Matt Boyle for sharing, and then posting, his talk, for prompting this post, and for critical discussion of its theme.

A notable exception is Mellor’s essay, co-authored with Tim Crane, “There is No Question of Physicalism.”

Kieran, I like where your mind takes me. I doubt aporia is quantifiable, but I seem to live with a lot of it—a kind of persistent overwhelm, even though my life is good and unreasonably stable.

I get lost in the philosophical weeds quickly when talking about Mind and World, real and circular and definitions. Pretty soon we are into McDowellean thinkables and Fregean thoughts, and I’ll never post a comment. We seem we wonder how our thoughts have a grip on the world. Maybe McDowel is saying that grip is already built into our thoughts?

Your project of seeking "real definitions" reminds me of Professor Elijah Millgram’s view that the mind’s job is to run a defeasible inference engine under severe resource constraints, and philosophy’s job is engineering our intellectual tools for doing so.

Anyway, I better post this now. I hope to come back if I can find my way out of the weeds. Meanwhile I’ll bask in aporia.

Gary

How is it possible that some philosophers feel "how possible?" questions are so compelling?