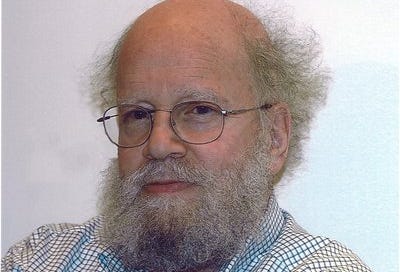

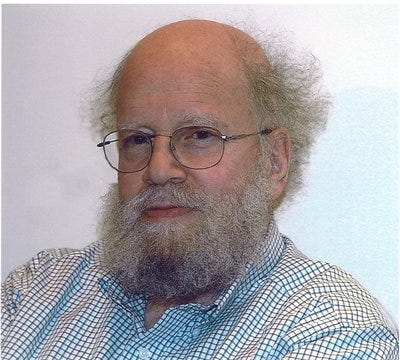

Michael Stocker (1939-2024) died this month. He was a pathbreaking moral philosopher who wrote (at least) three essays every ethicist ought to read: one about the dangers of moral theory, one about wanting what you think is worthless, and one about the reasons of friendship. He also wrote two brilliant books: Plural and Conflicting Values, and Valuing Emotions (with his wife, Elizabeth Hegeman).

I met Michael twice and liked him a lot, though I did not know him well. He wrote as an academic, but his prose was always vivid, and personal, and emotionally engaged. His topics were close to life. He argued, for instance, that the rationality of friendship does not fit the model of means-end reasoning: “because he is my friend” does not reduce to a goal or purpose I pursue.

Michael’s insight informed the treatment of loneliness and love in Life is Hard:

When I visit you in the hospital, there’s a difference between doing so for the sake of our friendship and doing so for your sake. I imagine you’d be hurt to learn that I came to visit only to maintain the relationship, or because friendship demands it, not out of direct attachment to you. As the philosopher Michael Stocker points out, “Concern for the friendship is different from concern for the friend.”

Michael wrote with feeling even in such mundane contexts as a book review. Here he is on Thomas Hurka’s analytic adaptation of “perfectionism”—on which a good life is one that realizes human nature:

I was very unhappy about much of the first two-thirds of Hurka's book, although I was very moved and impressed by the last third. … I am quite attracted to one of the main perfectionisms we know—Aristotelian ethics… What attracts me to that way of doing ethics makes it difficult for me to sympathize with a great deal of what goes on in contemporary ethical theorizing. … I think that my concerns and ways of doing ethics may unfit me for understanding or even commenting on Hurka's book.

This is not false modesty: the review is genuinely open to the prospect that Michael is missing something, even as he argues to the contrary. Apart from Hurka’s tendency to go on “in the modern manner,” Michael faults his focus on the rationality, as opposed to sociality, of human beings.

Further lacking in Hurka's account of human nature are various pleasures, games, celebrations, amusements, contests, religious or spiritual activities, much of aesthetic worth, quiet chats about little of consequence with friends or acquaintances, and so on. Perhaps we can imagine human life without these. But I do not think we can imagine good human life—life worth living and perfecting—without them.

Michael’s writings manifest an empathy for human experience in its diversity and difficulty. I once proposed a passage from his essay, “Desiring the Bad,” for a motivational speech:

When I consider people who see no hope for themselves or those they care for, who lack physical and spiritual energy, I am not at all surprised that—as political and anthropological data suggest—they may not seek even what little good they do perceive. Life may be too much for them. We, on the contrary, see the world as open to us, and more importantly, open for us. We can progress. We can make it. We see ourselves out there to be won. We have self-confidence and hope. Indeed we have more than this: we have an optimistic certainty. We have energy. We know we are worthy. We know that, barring bad luck, our enterprise will be rewarded. And so on.

Do “we” really think all that? The final sentence gives the game away: these are clichés copied from greetings cards—not truths we recognize but things we say to ourselves, sometimes, to inspire ourselves to act.

Just as often, what inspires us is not something said, but someone. Michael Stocker was an inspiration to philosophers, like me, who aspire for an ethics that is true to human life. I am sorry that I never got to know him as a friend.

Nicely done, and a good thing to do. Kudos.