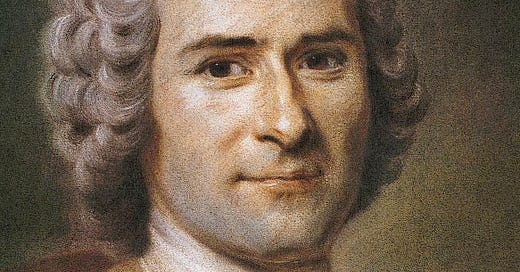

In the last two years of his life, embittered and paranoid, Jean-Jacques Rousseau embarked on a writing project for himself alone: ten essays that record the thoughts that occurred to him as he strolled through the outskirts of Paris, Reveries of the Solitary Walker. There is no evidence that he ever intended to publish the Reveries, and it would have been paradoxical to do so, given their explicit credo:

Everything outside of me is from this day on foreign to me. I no longer have any neighbours, fellow men or brothers in this world. Being on this earth is like being on another planet onto which I have fallen from the one on which I used to live.

Rousseau blames his estrangement on others:

The most sociable and loving of human beings has by common consent been banished by the rest of society. In the refinement of their hatred they have continued to seek out the cruellest forms of torture for my sensitive soul, and they have brutally severed all the ties which bound me to them.

But his ego…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Under the Net to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.