Q & A

We are all potential anthropologists of our own professional tribes: embedded for years or decades, observing the curious customs of the tribesfolk, absorbing the unwritten rules. Does anyone ever “go native” to the point that they cannot step back and sense the peculiarity of their tribe’s distinctive praxis—as Horace Miner memorably did in “Body Ritual Among the Nacirema,” which is not just about American relationships with bodily appearance, but a commentary on anthropological method.

I won’t attempt to copy Miner’s inimitable essay. But I’ll try to take a distant view of a ritual at the heart of academic philosophy: the post-talk Q & A. I’ve written about the talk itself before, comparing its format, only partly in jest, to that of a standup special: 50 minutes of prepared material, delivered live, intended to engage and edify a captive audience. My non-facetious point was that philosophers, unlike comedians, don’t think enough about the shape of the event. What is this format well adapted for? What are its strengths and limitations as a mode of performance? How do they line up with the aims of philosophical interaction? Perhaps the talk should change; or the content should be changed to suit the form.

Responses to my post were generally constructive. But there were objections. One noted that my simile was incomplete:

Interesting post! The strict analogy between stand up and a colloquium would be if a stand-up was doing their act for a room full of other stand-ups. Imagine Seinfeld doing an act with an audience of Chappelle, Chris Rock, etc. and two dozen junior stand-ups who want to have careers like Seinfeld and Chappelle. Would any sensible stand-up accept such a gig, let alone have that be the main form of performing their art?

I was reminded of a sublime performance by the Canadian comic Tony Law, which opens by acknowledging its unusual audience:

I’m glad they got my rider. … You’ve got to guarantee me that at least 40 to 50 percent of the people in have something to do with the comedy industry in some way. … I find that relaxes me. … I want half the audience to be jaded and tired of comedy. That’s how I get into my groove.

A second objection was less friendly: “I suspect you’ll get supportive comments that are disproportionate to the number of actual supporters,” it complained,

because admitting you’re not brilliant (in the kind of way that allows you to shine in less structured contexts) is uncomfortably close to admitting you’re bad at philosophy. Maybe that’s right. I’d like to believe there’s more than one way to be respectably good, though (I would, wouldn’t I) and wonder if further promotion of the already dominant conception of brilliance is really in the interests of the profession, its members or of the pursuit of truth.

Now, I don’t think I argued against structure in favour in ad libbed genius: one of my suggestions was a read-ahead format, where the “presenter” is required to do less live entertainment, not more. But this would still involve an interactive Q & A—without which it’s not clear why we’d bother having visitors at all. And in the Q & A, a certain kind of brilliance is prized: speed of thought in response to unexpected questions, or the display of mastery that consists in having thought of them before, three steps ahead of one’s bedazzled audience.

In the terms of my analogy, the Q & A is structured heckling, in which an audience of comedians attempts to be funnier than the comic on stage. That’s how it used to feel, anyway. The culture of the philosophy Q & A in the 1990s, when I went to school, was competitive to the point of being zero-sum: the host philosophers would assert their dominance over a visiting speaker by refuting their arguments, or at best admit to an honourable draw. Both sides were on offense.

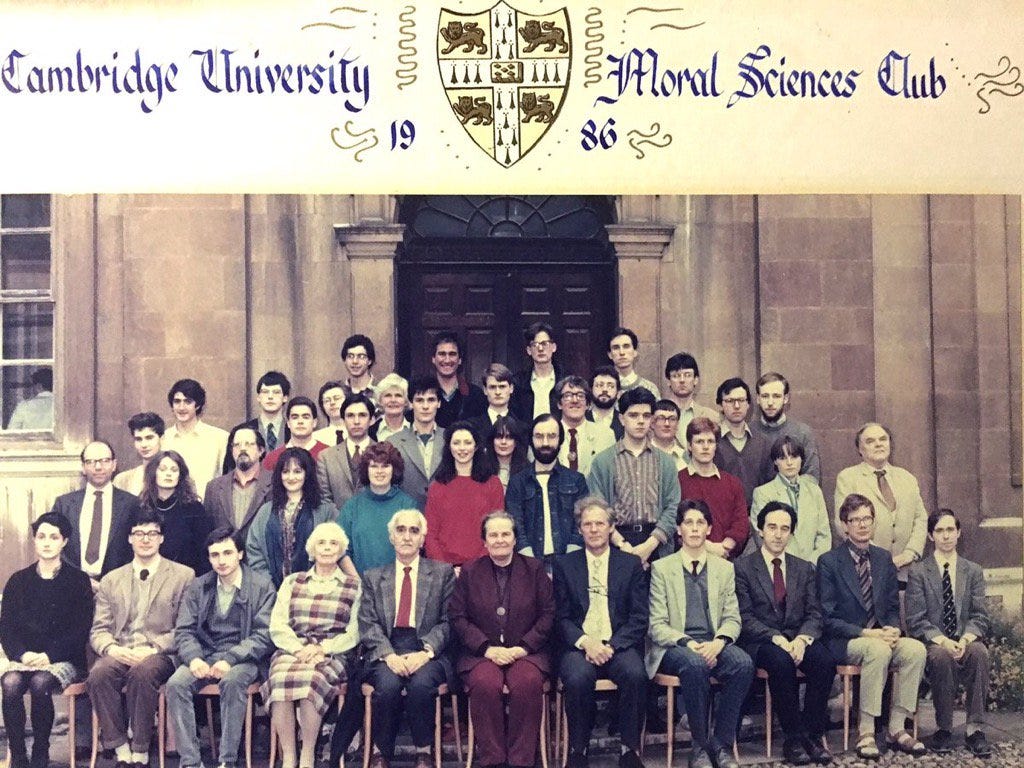

Sometimes, the dogfight was transparent. I remember a session of the Moral Sciences Club at Cambridge in which the Chair broke up an unusually constructive conversation by calling on a colleague who hadn’t raised his hand but could be counted on to lower the tone. The first question I had the courage to ask, myself, as an undergraduate, objected to a speaker’s reading of the “private language argument.” I will never forget the response:

This is the problem with Wittgensteinians: you say something clear and they pour soup over your head!

Even the helpful comments, which were rare, could feel like reassertions of the pecking order. They remind me now of Samuel Johnson on self-condemnation: “All censure of a man's self is oblique praise. It is in order to show how much he can spare.” Yet more rarely, a visitor would draw attention to the combative ethos: “If this were a boxing match,” a speaker at Princeton once remarked to a relentless interlocutor, “the referee would have stopped the fight.”

At least in my experience, however, the culture of the Q & A has substantially changed in the last thirty years. There are still objections to arguments, but the tone is generally less hostile, constructive comments are not as uncommon as they once were, and audiences are more willing to let a line of questioning drop when it’s clear that the speaker has no more to say. The “attack dog” mentality is sufficiently unusual nowadays that I am shocked when it shows up, as it sometimes does—like seeing a man in the audience wearing a bowler hat: “Ah, so people still do that!”

All the same, this welcome shift in style makes for less clarity about the function of the Q & A. If you had to defend the old system, you would say that a practice of ruthless refutation serves the collective benefit of all: it’s an efficient way to improve the quality of arguments across the intellectual ecosystem. By attacking one another, we help each other, as the invisible hand of the market makes competitive self-interest a means to the public good. I’m not saying it works; but that’s the theory. Even if it does work, the cost of creating a “morality-free zone”—an unregulated market, a ruthless Q & A—is greater than the system’s architects should have hoped.

But now we face a question: what exactly is the function of the audience Q & A, in its more recent form? Is it meant directly to improve a speaker’s work, in which case we should devote as much time to answering objections as we do to raising them? Or is it pedagogical: that we all learn more about the topic?

I’m not saying it’s bad that the practice is less well-defined, but it creates uncertainty about the norms—and about the extent to which the Q & A is, as we might put it, “ordinary human interaction.” For instance, should you thank the speaker for the talk and politely praise it before asking your question? In ordinary human interaction after the talk, you should say “Thanks, that was really interesting!” But wouldn’t it be more efficient if, in the special context of the Q & A, we took this acknowledgement as read and used the extra seconds, aggregated through an hour, to fit in one more question? Or does this policy downplay the cost of killing everyday politeness?

Other conventions are up for grabs. There are still questions you are not supposed to ask, for differing reasons.

What is the strongest objection to your view, the one you are most worried about?

Why is this topic interesting or important?

How did you come to work on this?

The third question is too biographical; the second could be obnoxious; but the first would often be terrifically productive for the Q & A. And yet it’s disallowed. (The colloquium dinner is much freer in these respects, which is why I love it so much—a model for my podcast.)

I close with a report from a recent colloquium, written by a Martian anthropologist:

Although it opens with applause, the ritual seems to be masochistic. The faces in the audience are grim or grimacing, at times suggesting that the speaker has emitted a foul odour: noses wrinkle in disgust. Other times, oddly, there are laughs, though they are brief and do little to lift the mood of laboured concentration. The audience make minimal eye contact, shifting uneasily in their seats or reading the papers they collected as they came in. These pamphlets are slowly defaced with scribbles, symbols that perhaps encode a charm to ward off threats of which the speaker warns.

Close to an hour, the audience claps and the room empties out, the orator left standing, awkward and alone: ostracized or punished for their words? Those who remain stare mutely at their papers or whisper in conspiracy with neighbours.

When the audience returns, the second half begins: hands raised aggressively, counted by a bookkeeper who tallies them—some kind of vote?—then lowered, as the accountant calls on voters one by one. They make speeches, but their character is obscure: some smile, some frown; some speak briefly, others at great length. The catechism has two sides: after each intervention, the visitor responds—under evident duress. Perhaps the first speech was an apology, and this is their trial? But that does not explain how things come to an end, with more applause and smiles of relief all round. The ritual, whatever it is, has done its cathartic work.

It is so helpful to see someone think about this from a different discipline, because I think about the related questions in history all the time. Those questions being, I guess, 1. what is a talk/q&a for, 2. how might it be more usefully organized, the meta question of 3. why don’t we do it in a more useful way, and I guess also the meta-meta question of 4. why colleagues don’t ask the first three more often.

Except, and I do not say this in the Samuel Johnson humblebrag way, I think it’s all kind of worse in history. That’s because historians tend to frame our claims in such specific and local ways, and we are allergic to making broader claims. It’s not even all that common for someone to frame their work as “this other interpretation is wrong.” The intended relation of a given talk or paper to others about the same subject is therefore unclear, let alone to people in different subfields. With very rare exceptions we don’t have access to the evidence a presenter is using, and in fact part of the performance is to show how you've found and used some previously-obscure source. So the questions are usually of the "I'm curious, can you say more about that?" variety, with a few of "based on what you said, maybe there's a different interpretation" sprinkled in.

The result is that even within a subfield, unless a speaker’s work directly ties in with yours, their presentation is unlikely to have any meaningful influence on your aork, other than perhaps to add as a footnote somewhere. And for most of the people in the audience, the overall effect is even more limited, a perfectly pleasant "huh, interesting."

I'd like to think we can aim higher. But part of that would mean almost deeper retraining, so that historians make more ambitious and generalized claims in talks or papers, even at the risk of being shot down.

Thank you for the pointer to the Nacirema paper—that’s going right into my American Studies syllabus. Do you know “An anthropologist among the historians” by Bernard Cohn? From 1962, but still hilarious and devastating.

A quote from a former department chair at my grad program about the Q&A: "If you don't have anything not nice to say, don't say it at all".

But it almost never got around to personal attacks or insults. Hard, pointed, you're probably wrong about this, questions., but fair ones. Indeed, a personal attack would have been ridiculed by the audience. It's not why we were there.