No Entry

It shouldn’t be surprising that critics have wanted to read Doors—Christian Marclay’s looping montage of movie clips, in which one protagonist enters a door and another steps out, seamlessly, over and over again—through the lens of new media, specifically AI.

Marclay is famous—perhaps too famous—for The Clock, a 24-hour sequence of minute-long excerpts, smoothly stitched together, each of which references the time at which it is being shown, so that, if you watch at 8:55, a watch or clock in a film clip shows “8:55,” or a character mentions that time. Reviewing Doors as a sort-of-sequel, Anna Schechtman writes:

If The Clock inspired thousands of spectators to ask, “How did he do it?,” Doors might now compel the same to wonder, “Could AI do it?”

Carlos Valladares is more brutal:

What was until recently less apparent while face-to-face with The Clock’s sublime blah-ness, but which is all too plain in Doors, is how slavishly in thrall Marclay’s works are to the principles now touted by A.I., the way it decontextualizes, corrals, and amalgamates moments into a machinelike order. Up until recently in the short history of cinema, an image cut together with another image could potentially create new meaning in a shiver-inducing manner. But in the TikTok/GPT era, a cut bringing together unmoored images hits the viewer with the force of a shrug and a meh. With The Clock, Marclay predicted this mediascape all too beautifully; with Doors, he belabors the obvious.

Perhaps I’m not sufficiently online—I don’t use TikTok or ChatGPT, for instance—but that wasn’t my experience watching Doors at the ICA in Boston this July. The self-selecting audience did not seem to shrug, but to delight and puzzle over the resuturings. Each transition is at once sharply discontinuous—our protagonist transmutes into a new identity, sometimes changing gender and, occasionally, number, becoming plural, as a posse tumbles into frame—and at the same time perfectly smooth, matching the kinetics of the door, the momentum of the body moving through it, or knocking at it, the perspective of the camera.

At a certain point, one begins to notice repetition, at first of clips then, more rarely, of transitions. Sydney Poitier keeps entering the same school corridor, the doorway flanked by a crowd of kids; he strides with severity down the hall to his exit, each time transforming from and to another person in another place—a farce that eventually elicits inappropriate giggles.

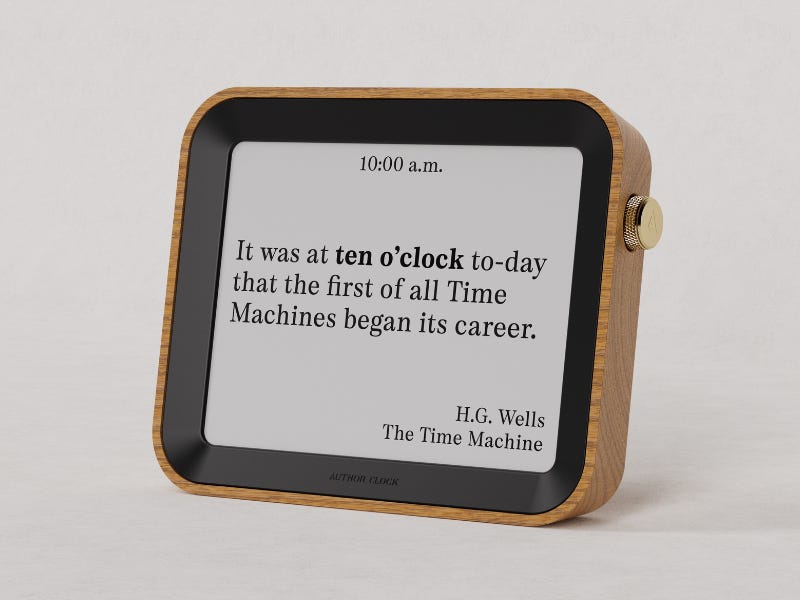

No doubt critics run the risk of becoming jaded. And it’s true that The Clock now feels routine to the point of commercialization. It even inspired a Kickstarter campaign—full disclosure: I contributed—that produced the Author Clock, which tells time, minute by minute, with quotations from novels.

As Valladares complains, Marclay’s installation has become an “event”: “circuslike crowds will always amass whenever The Clock arrives in a city near you.”

But the arty point is obvious: in real life and especially in films, time is a fantastical construct that nevertheless rules our lives. Ya don’t say!

Yet reading Doors as a manifestation of, or at best a commentary on, new media feels like a way to limit one’s experience of it, not to enter it wholeheartedly—going “meta” too soon. Maybe some cannot help but do that, saturated as they are in up-to-date technologies of visual communication, but if so, that is itself a manifestation of, or a commentary on, new media: its tendency to close the door to a less filtered mode of experience.

Not every critic understood Doors as a critique, or casualty, of AI video manipulation. What did those who declined to go “meta” find within it? Mostly claustrophobia. The mutable protagonist of Doors is trapped inside an endless labyrinth, and we are trapped with them. There is no hint of any outdoors, and because each clip is brief, we are constantly hemmed in by tight spaces, doorways and corridors.

At least two critics called the viewing experience “a nightmare” or “nightmarish,” and they are not exactly wrong. Especially at the start, the atmosphere is anxious, taut, uncertain. It’s not an accident that Doors was completed during the pandemic lockdowns.

But as I came to learn the rules of the game—which Marclay bends, at times, allowing a protagonist to pass through a door intact, or using a flashlight as a metaphorical door into another world—I began to feel safer. Reality is eternal and predictable; every door leads somewhere; we can always return and always will. The presiding affect of Doors is comic, not tragic: chase sequences take on a Keystone Cops quality, and every cut is a visual joke, sometimes amplified by an auditory one, as sounds from one world—music, an alarm or siren—leak into another.

The sense of confinement is subverted, metaphysically. Yes, we are confined in space and (looping) time, but we are liberated from identity, even from being one as opposed to many. Each film is a self-contained world, but we can leave any given world—in fact, we are compelled to—alighting on another focal character, like a thought experiment about persistence through time in which we seem to be no more than loci of consciousness or angles of perspective on the world.

Doors is an enforced liberation from oneself: in time, it induces resistance. What I found myself wanting, after an hour or more, was not to leave the maze, or to go out-of-doors, but to stay where I was for more than thirty seconds, to be someone in particular for a while, to see what happens next in this world, not another.

When you decide to exit Doors, at a moment that can only feel arbitrary, passing through the doorway from the dark into the light, this fantasy of freedom is fulfilled.

A Marclay opening:

https://discontinuednotes.com/2023/09/05/conduits/

Back in my day we didn’t need ai we just had good ol fashioned autism