Composition with Grid

A few months into the pandemic, my wife and I adopted a new pastime: we would complete the New York Times crossword puzzle every day. The puzzle gets more difficult as the week goes on, Mondays being easiest, with the qualitative peak on Saturday and the quantitative Sunday, when the crossword is nearly twice as large. It got tricky for us by Thursday—but, we reasoned, our crossword muscles would grow stronger with practice, and we would soon be adepts, puzzling together in harmony through our declining years.

We were partly right. It did get easier—but we were not harmonious. Turns out, there are different styles of crossword-solving, and my wife’s Brownian motion, bouncing erratically from clue to clue without rhyme or reason, I found intolerable. We tried taking turns, but I was so distracted by her chaos I could not collaborate. We shifted to parallel play, but her diligence lapsed, and I now do the crossword alone, each day, in solitary absorption.

At the time, we both agreed: this episode did not speak well of me. But recent work on the art of crosswords sheds new light. Writing in the British Journal of Aesthetics, the philosopher Robbie Kubala—who has finished in the top 25 in the American Crossword Puzzle Tournament—argues, in the face of a dismissive scepticism, that there is aesthetic value in at least three elements of puzzling:

The experience of harmony, capacity, even the sublimity of failure in one’s own agency.

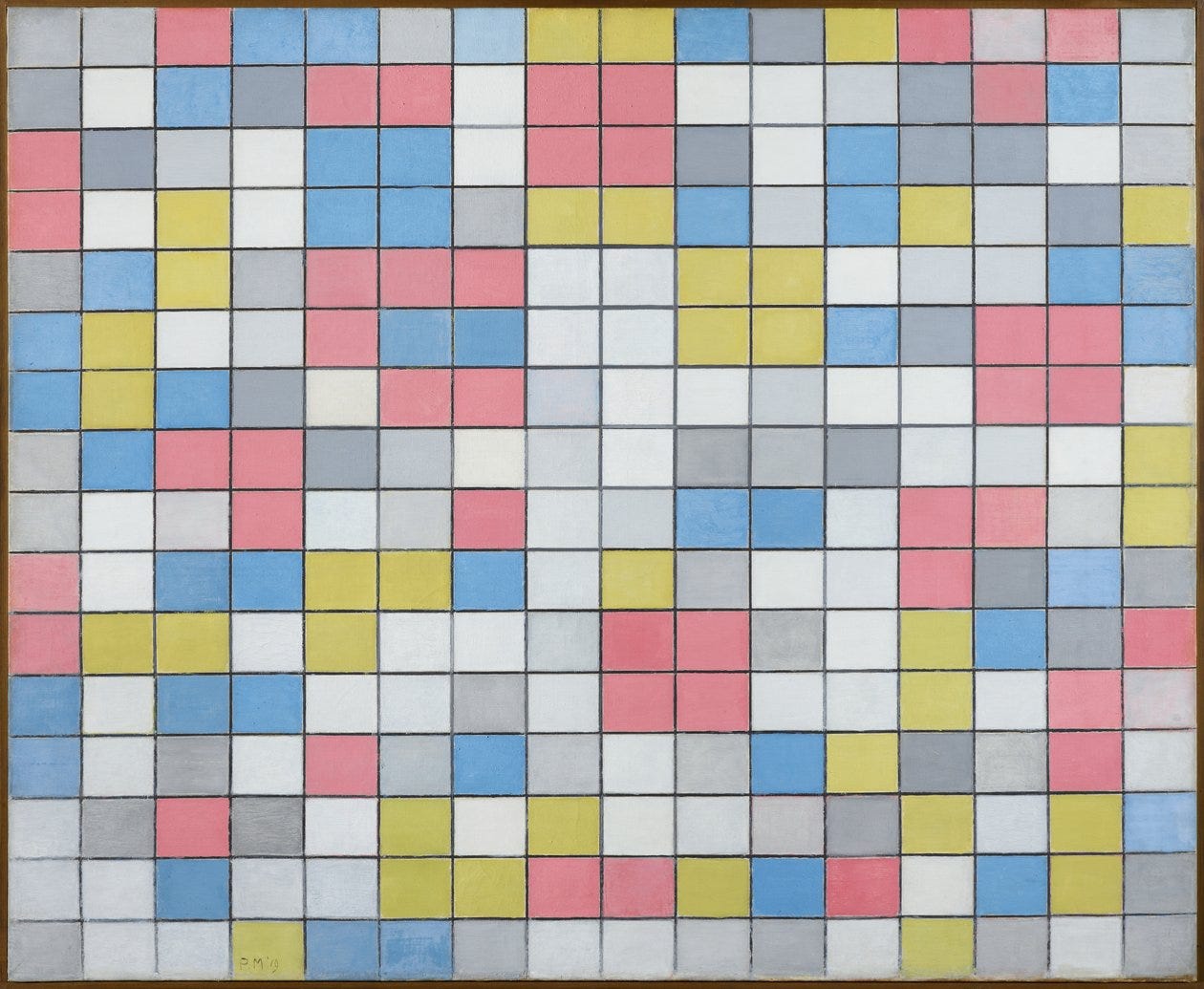

The visual beauty of the grid—described by Adrienne Raphel as “a cross between a Mondrian and latte art.”

The creativity of wordplay.

If Kubala is right, my wife’s style can be criticized on aesthetic grounds, obstructing harmony in the exercise of joint action. My approach, in contrast, guided by sensible rules of thumb—start with one across; when you find the first letter of an intersecting word, check the corresponding clue, etc.—is more elegant, more orderly, and more artistic. I can’t wait to tell her!

I gained other insights from Kubala’s work. Did you know, for instance, that Stephen Sondheim introduced the British “cryptic” crossword to America in 1968? A cryptic clue includes a definition, an elliptical hint, and a letter-count—nothing more. Sondheim gives a nice example: “Stares at torn pages (5).”1

Before Sondheim brought the cryptic crossword across the pond, the puzzle was exported to the UK from the US, soon after the very first published crossword, by Arthur Wynne, in the New York World, 1913. According to Roddy Howland Jackson, the Brits were alarmed at the ensuing craze: five million hours a day of wasted labour. Public-access reference works were so drastically overused they had to be withdrawn from circulation, with predictable results: “Thesaurus sales skyrocketed while library use crashed.” I would be the last to bemoan an upsurge in thesaurus ownership; but I consider its use a form of cheating.

The association of wastage with the crossword was endemic. In 1925, an article in the New York Times called it “a sinful waste … utterly futile.” And in 1939,

a poetry critic at the Birmingham Daily Gazette could not decide if Eliot’s masterpiece was cryptically brilliant or merely an overwrought cryptic: “‘The Wasteland’ may be a great poem; on the other hand it may be just a rather pompous cross-word puzzle”.

Eliot himself enjoyed crossword puzzles and was delighted to be referenced in one—maybe, “African fly that doubles as a poet, in brief? (6)”2 Would he have welcomed the comparison, which can be read against the grain, finding beauty in the not-so-pompous crosswords millions complete each day?

While the exercise of agency is one site of beauty in crosswords, and the appearance of the grid another, I suspect most crossword addicts take pleasure, primarily, in wordplay: the ingenious splicing of signs, the spark of brilliance in a pun or riddle, the MacGuffin that connects the clues of a thematic crossword, unlocking their secret. By the same token, we come to hate the tired reuse of convenient crossword fillers: spare me another “Oreo,” New York Times!

The art form most palpably adjacent to the crossword is almost as neglected: the joke. Kubala does not make much of puzzling humour, but Sondheim did.

To call the composer of a crossword an author may seem to be dignifying a gnat, but clues in a “British” crossword have many characteristics of a literary manner: cleverness, humor, even a pseudo-aphoristic grace. … Railway coaches, undergrounds, lunch counters and offices in England hum with the self-satisfied chuckles of solvers who suddenly get the point of a clue after having stared at it for several baffled minutes.

Laughter is an apt response to solving certain crossword clues: pleasure in the sudden dissolution of incongruity. (Check out the pun at the heart of this New York Times puzzle, by my wife’s first cousin once removed.)

In their monograph, Inside Jokes, Matthew Hurley, Daniel Dennett, and Reginald Adam contend that all humour has this form: it’s the pleasure we take in detecting covert error in active beliefs, resolving misdirection. I don’t think that’s true, in general. It doesn’t make sense of repeating jokes, where misdirection is no longer active. It struggles with insult comedy. And it omits the comedy of the absurd, in which incongruity is joyfully unresolved. Here’s a moment with a master, Noel Fielding, from season 8 of The Geat British Bake Off:

I’ve got a little Portuguese fact for you: Portuguese footballer Christian [sic] Ronaldo once fired a custard tart out of a bazooka, stunning a chaffinch in flight. So bear that in mind as you’re making your tarts.

Still, the Inside Jokes account is apt for crossword clues, when they are funny. They give the pleasure of a puzzle solved—the more deceptive, the funnier.

Kubala begins his essay on crosswords with reflections on the puzzle, via Thomas Kuhn, for whom a puzzle is a problem with “the assured existence of a solution” in the presence of “rules that limit both the nature of acceptable solutions and the steps by which they are to be obtained.” He cites, also, an unpublished paper by Kenny Easwaran, which proposes that a puzzle contains a means of double-checking.

We call a problem in philosophy a “puzzle,” I suggest, when it meets Kuhn’s two conditions, as when we formulate an inconsistency and ask: which claim is false? We know there must be a solution, even if we can’t be sure it will be found; and the rules of the game are relatively clear. What we don’t have is a way to double-check: to confirm, if we solve the puzzle, that our solution is correct.

If Hurley et al. were right, we could not be amused by puzzles like this, since we could not, in the relevant sense, detect our error. But this is to sell the sense of humour short: paradoxes can be funny. On the other hand, it would be too much to say, with Georges Bataille, that “a burst of laughter is the only imaginable and definitively terminal result … of philosophical speculation.”

We are looking for a synonym of “stares” for which “torn pages” is a circuitous clue: rearrange the letters of “pages” to make the word “gapes.”

The word “tsetse” consists of T. S. Eliot’s initials, doubled.

Oh for a dearth of Oreos! I’ve decided it has to be a joke with puzzle constructors at this point. “Alright, I’ve added the Oreo. Now to find a place to mention Yale…”